*folds world map in half

*sticks pencil throughI honestly believe that sometimes, my genius, it generates gravity.

You youngsters with your Einstein Rosen-bridges! Always in too much of a hurry to take the scenic route!

deleted by creator

HYPERSPACE

Reminds me of the movie Event Horizon.

And like 5 million other movies

Low IQ: it’s not a straight line

Medium IQ: it’s a geodesic on a sphere, so it is a straight line

High IQ: it’s not a straight line

He’s right, you know.

About the line?

About everything, damn it!

It’s a straight line through non-euclidean space

unfortunately in reality it is a curved line on a sphere

In actual reality there would be wind and water currents diverting any ship sailing that route from the depicted “line” anyway so the whole argument is pointless

The only straight line paths in the universe are followed by electrostatically uncharged non-accelerating objects in free fall in a vacuum. Or massless particles.

What if we assume the ship is actually a spherical cow

Nuh uh. My fifth grade math teacher told me that if I drew a line with an arrow on graph paper and no other line intersected it, that it would continue on into infinity!

Whole Universe eh? That exists and is bounded on a curved space time.

I’m just joking, but you can really take this to the extreme lol

Spacetime is curved. Inertial paths through spacetime are straight.

Euclidean space is not the only space where straight lines are possible.

It can get a few percent longer if sailing between Madagascar and the rest of Africa but Pakistan-Russia does not have the same ring to it, I guess.

Edit: source (German), they also show the longest land route (across Eurasia of course)That’s not a straight line, although it is possible to follow without changing direction😊

I KNOW IT’S BASICALLY A CIRCLE IN 3D SPACE. There is an exact amount of pedantry at play here, and you’re going over.

Would you say that they… crossed the line?!?! 😏😏😏

In our space time frame of reference, we never change direction, we travel in a straight line. It’s a straight line.

And when Im walking, in my frame of refrence, the houses on the side of the road move behind me. Houses move.

But following the surface of a sphere causes you to constantly change direction

Correct! Technically :P

deleted by creator

Would straight plane be as understandable?

Dude that’s awesome. How did you make these images??

I didn’t, it’s from a spiegel.de article

Ridiculous. This line is clearly gay.

This is bi erasure.

Not even 10 am and I’m being erased.

Never thought I’d get to use “bisectional” outside of JD Vance jokes

Saying that it’s bi erasure is gay erasure.

We claimed it is erasure first, and now here’s our flag.

Hey, you even have the eraser right there is the middle! I suppose that makes it convenient?

I really do love convenience!

Lmao at the admission that the entire identity of being bi is claiming erasure and playing victim.

It’s bi sectional.

This whole map is woke.

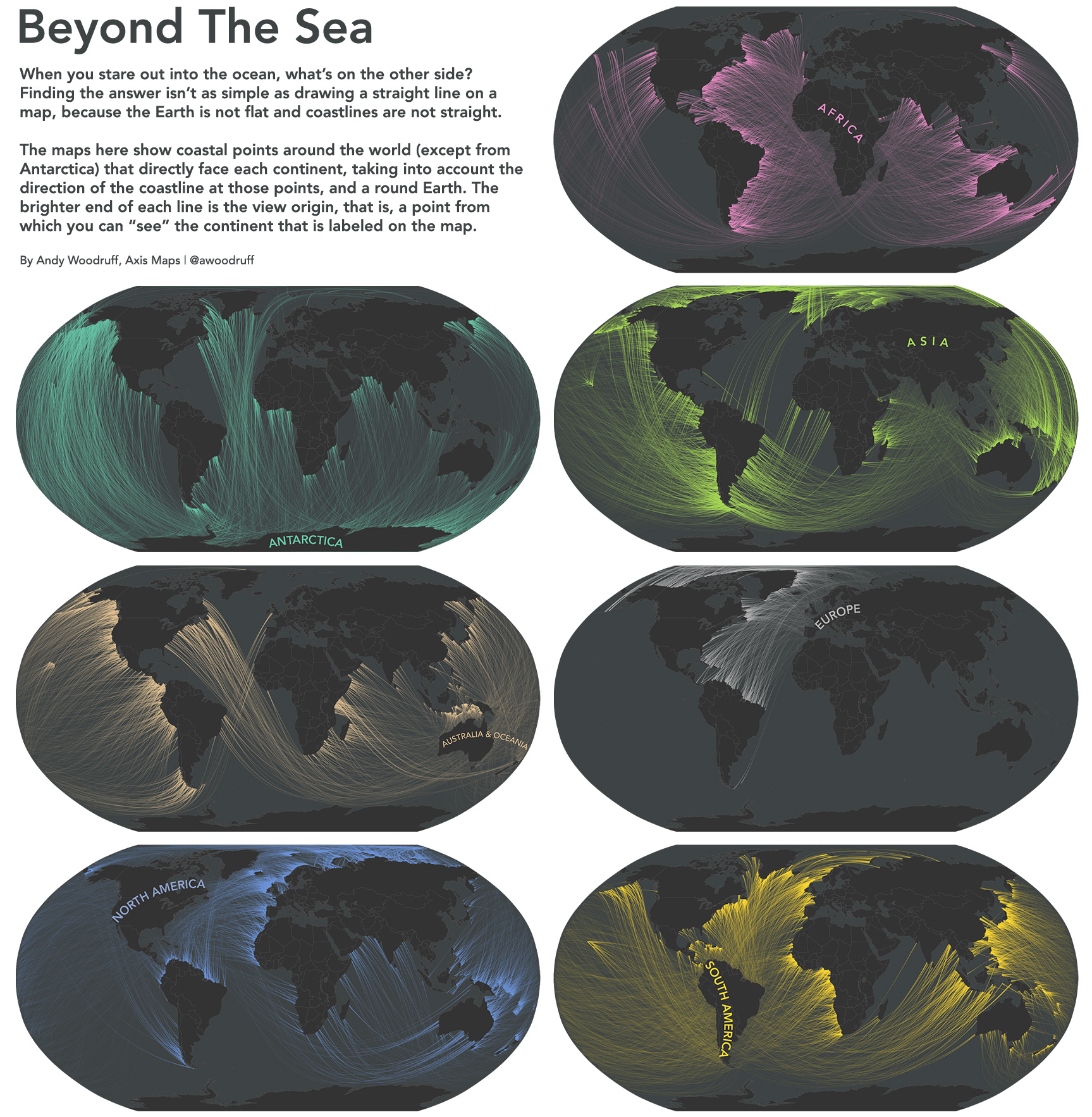

This reminds me of some maps by Andy Woodruff.

They weren’t made to find long lines, and picking out a single line can be a tad difficult, but it’s very interesting nonetheless.

South America’s reach is incredible, compared to size that is

And it’s mystery is exceeded only by it’s power.

Well there’s the one guy in Northern India who gets a peek at South America from between Madagascar and the African continent.

There is also just the one straight path from the US east coast (Florida) to Asia.

Today on the internet: Fun with spherical geometry.

Your dad and I think you should start looking for a job.

I can’t legally work in my country I’m not old enough

But still, don’t you hunger for the mines?

Fuck it

Eats the mines

Toiling in the meme mines.

Edit: I have just finished reading The Neverending Story and this reminds me of the last part where Bastian works in the picture mines until he finds the right picture.

Space-time itself is curved, therefore there is no such thing as a straight line.

Not true, as when space bends, it bends the rulers and compasses too. We experience no spatial distortion.

A person traveling near the speed of light doesn’t feel like time is slower for them (but it is and we can measure it)

The principle is equivalent.

That said, it’s not a straight line in any topology standard I am aware of.

Sure you could CREATE a topology framework where this would be considered a straight line, but there is no real world model that could come even close without so much mass being concentrated in static relative areas, and EVEN THEN it would only be straight for a predetermined instant before the mass deforming spacetime began interacting with each other.

That’s the problem with spacetime deformations, almost no layman takes into account the ridiculous amounts of static mass to make those strange topologies.

Space-time itself is curved, therefore everything is moving in a straight line, it only appears to be curved to the outside observer

We have geodesics for that.

If anyone wants to grasp the basics: here is some fun reading (leading on to some beautiful math). Changing the idea of parallelity leads to hyperbolic geometry and other fun stuff. :)

Please correct my layman understanding if I’m wring here. But isn’t everything traveling in a straight line until an external force is applied. For example the earth orbiting the sun is traveling in a straight line in a curved apacetime. Also if you jump, the moment you leave the ground until you touch it again coming back down you were traveling in a straight line.

I dunno lol

Also if you jump, the moment you leave the ground until you touch it again coming back down you were traveling in a straight line.

relative to the body of earth, including its rotation it would be an arc path, and including it’s tilt it would be 3d, if we also include the travel around the sun in orbit, that elongates it around the orbit, so uh.

In my understanding, since gravity is acting on us, an external force is applied when we jump. That’s why a jump is a parabola. “Gravity’s Rainbow”

What they are getting at is that gravity is not a force so much as your mass trying to travel in a straight line through curved spacetime. The weight you feel is because the surface of the earth is in your way.

Get into low earth orbit and that straight path has you going in apparent circles around the planet. You are very much within the earth’s gravity but you don’t feel “weight” because the surface of the earth is no longer blocking your path. You still have mass and inertia and all that, of course.

Yes, that’s exactly what I meant :D

How can any line that is on the surface of a sphere be straight rather than a curve?

Haa, here people, we found a flat earth denier…

Earth is a lie.

GET THE ROUNDIE!

it’s a bit of a “spirit of the law vs letter of the law” kind of thing.

technically speaking, you can’t have a straight line on a sphere. but, a very important property of straight lines is that they serve as the shortest paths between two points. (i.e., the shortest path between

AandBis given by the line fromAtoB.) while it doesn’t make sense to talk about “straight lines” on a sphere, it does make sense to talk about “shortest paths” on a sphere, and that’s the “spirit of the law” approach.the “shortest paths” are called geodesics, and on the sphere, these correspond to the largest circles that can be drawn on the surface of the sphere. (e.g., the equator is a geodesic.)

i’m not really sure if the line in question is a geodesic, though

You are absolutely correct, but to add on to that even more:

When we talk about space, we usually think about 3D euclidean space. That means that straight lines are the shortest way between two points, parallel lines stay the same distance forever, and a whole bunch of other nice features.

Another way of thinking about objects like the earth is to think of them as 2D spherical manifolds. That means we concern ourself only to the surface of the earth, with no concept of going below the surface or flying up into the sky. In S2 (that’s what you call a 2D spherical manifold), and in spherical geometry in general, parallel straight lines will eventually cross, and further on loop back and form a closed loop. Sounds weird, right? Well, we do it all the time. Look at lines of Longitude, for example.

We call the shortest line connecting two points in curved manifolds geodesics, as you said, and for all intents and purposes, they are straight. Remember, there is no concept of leaving the sphere, these two coordinates is all there is.

What one can do, if one wants to, is embed any manifold into a higher-dimensional euclidean one. Geodesics in the embedded manifold are usually not straight in higher-dimensional euclidean space. Geodesics on a sphere, for example, look like great circles in 3D.

Absolutly fantastic explination of how to conceptualize the complexities of geometry. Such an interesting area of mathematics

What is the slope of a straight line, a linear function? Now what is the slope of a nonlinear function, aka a curved line?

A geodesic would only be accurately labeled a “straight line” IF it was on a plane. On a curved or uneven surface it’s a nonlinear function.

i think it depends on what you mean by “accurately”.

from the perspective of someone living on the sphere, a geodesic looks like a straight line, in the sense that if you walk along a geodesic you’ll always be facing the “same direction”. (e.g., if you walk across the equator you’ll end up where you started, facing the exact same direction.)

but you’re right that from the perspective of euclidean geometry, (i.e. if you’re looking at the earth from a satellite), then it’s not a straight line.

one other thing to note is that you can make the “perspective of someone living on the sphere” thing into a rigorous argument. it’s possible to use some advanced tricks to cook up a definition of something that’s basically like “what someone living on the sphere thinks the derivative is”. and from the perspective of someone on the sphere, the “derivative” of a geodesic is 0. so in this sense, the geodesics do have “constant slope”. but there is a ton of hand waving here since the details are super complicated and messy.

this definition of the “derivative” that i mentioned is something that turns out to be very important in things like the theory of general relativity, so it’s not entirely just an arbitrary construction. the relevant concepts are “affine connection” and “parallel transport”, and they’re discussed a little bit on the wikipedia page for geodesics.

Thank you for the informative answer

This whole post is a good illustration to how math is much more creative and flexible than we are lead to believe in school.

The whole concept of “manifolds” is basically that you can take something like a globe, and make atlases out of it. You could look at each map of your town and say that it’s wrong since it shouldn’t be flat. Maps are really useful, though, so why not use math on maps, even if they are “wrong”? Traveling 3 km east and 4 km north will put you 5 km from where you started, even if those aren’t straight lines in a 3d sense.

One way to think about a line being “straight” is if it never has a “turn”. If you are walking in a field, and you don’t ever turn, you’d say you walked in a straight line. A ship following this path would never turn, and if you traced it’s path on an atlas, you would be drawing a straight line on map after map.

I think those last 2 paragraphs are due to people approximating math that would otherwise be quite complex to calculate, or making models that are approximations due to widespread available technology. Just because I don’t turn if I cross over Mt Everest, does not mean that is the fastest route by foot.

I’m not saying to not use these approximations.

I really recommend the book “Where Mathematics Comes From,” to really think deeply about what math is to us as an animal. Even other animals can do some rudimentary math, and arguably athletes are doing math innately as they perform their sports. Birds and dolphins do physics and calculus. Sort of. In this view, what we teach as math to each other as humans is essentially a language describing these phenomenon and how they work together. Calling this approximation a “straight line” in this language sense isn’t very accurate and it’s what’s causing the debate.

Stop making up bullshit to justify it. It’s not a straight line so don’t say that it is. Words have meaning.

By defining the coordinate system as a sphere.

Basically, there are multiple right answers, but the most correct answer depends on how you define coordinates.

In “simple”, xyz it’s not a line.

In Euclidean geometry, a straight line can follow a curved surface.

In bullshit physics, everything is warped relative to spacetime so anything can or cannot be a line, but we won’t know.

Yup, found the round earther.

Globists will argue that on a globe this is a straight line. Seen these arguments before, don’t work on me

Nice. Be proud.

Dunno what of, but be proud anyway!

Thanks! I’m very proud of seeing the truth. Watch this short video and you will being to understand. But watch it to the end, it’s short enough

The ending really brings the whole video together. Thanks for sharing!

You’ve made a believer of me.

I’ve seen that video a hundred times and it never fails to disappoint

You know, I’d never actually thought of it that way. Very informative video for it’s short length. Thank you for sharing.

One of the most compelling arguments I’ve heard. I must say I was a skeptic before but this really opened my eyes

Don’t know about other clients, but vger shows a thumbnail of the video

Better?

Got error: “Sign in to confirm that you’re not a bot”

Hmm, really makes you think…

Every line is a straight line in one dimension

Would clarifying words have helped? “If you only sailed with forward force…” or “Following along the surface of the earth…” or… what?

Obviously they mean that you don’t need to make any turns and that straight means an arc around the earth and not through the Earth, unless someone has a very different idea what sailing means…

Depends on what you mean by help. Yes, it would communicate the point better, but it’s engagement bait, so the ambiguity is a feature rather than a bug.

Yes I think they mean it’s a continuous line, not a “straight” line. As in the line is uninterrupted (continuous). It’s also possible they mean the line qualifies as a nonlinear function since it also doesn’t double back over itself (A function is a relationship where each input value (X) will create only one output value (Y)).

Math is hard. Describing lines like this is math - calculus actually due to the curve, and actually not just basic calculus but vector calculus because it involves an x,y, and z axis. Most laypeople will struggle to describe a line with the correct jargon.

Line that is straight in two dimensions.

deleted by creator

THAT would be one god damn brutal sail. Both horns, Southern Atlantic crossing followed up by the Indian Ocean.

The range of foulies you would need to bring would be 3/4 of your pack. Foulies underwear and A sock (you’re going to lose one anyways)

I assume you mean “both capes.” While this line does come within a few thousand miles of the Horn of Africa, that’s not known as an especially hard sailing area but maybe for pirates.

Sailing this line in the other direction would be considerably harder.

deleted by creator

Cmon man. Yes I’ve been a few places in sailboats. North sea in the winter for one. You clearly were trying to refer to Cape Horn and The Cape of Good Hope (or Cape Agulhas). Just take the L and don’t be a twat.

OMG I got a word wrong.

There was a conversation I read a while ago that showed how a sailboat could travel a straight line over water from Halifax, Nova Scotia in Canada, travel southeast and end up on the west coast of British Columbia.

Basically sailing from the east coast of Canada to the west coast of Canada in a straight line.

The line was published by David Cooke in this YouTube video. It lies on a plane but is not quite a great circle (in practice, you’d be turning slightly) and good luck sailing over the Antarctic ice shelfs this decade.